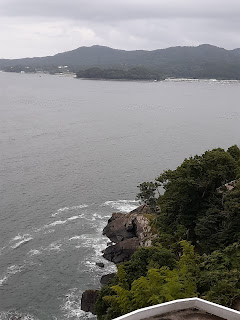

A piece of the Sanriku coast at Minamisanriku, NE Japan.

In 2011 there was a 20.5-metre tsunami here.

In 1966 the eminent Californian risk analyst Chauncey Starr published a seminal paper in Science Magazine in which he stated that "a thing is safe if its risks are judged to be acceptable." In effect, he built his reputation on the premise that the acceptability of risk is arbitrary.

Before I travel on university business I am required to fill in a complicated on-line form called a risk assessment. Recently, I had to do this before attending a series of meetings in Japan. By and large, Japan is a very safe country in which to travel and sojourn. By contrast, where I live in north London, within a radius of 400 metres of my front door, there have been at least two murders, a major and lethal terrorist incident, an international terrorist conspiracy, a series of road accidents, some of which were fatal, episodes of chronic pollution and overcrowding, and a constant battle between the police and a well-organised, wide-reaching drug supply ring. In the 1950s the area was immortalised in the photographs of Don McCullen, who was attracted by the presence of the London mafia.

When I travel from north London to my university I use public transport, which is of variable reliability. I then have to cross a busy four-lane arterial road. At one point the green light allows five seconds for pedestrians to scoot across, while at another designated crossing place they are afforded no protection at all against the streams of roaring traffic. At my university a problem with vibrating equipment caused bouts of deafness and nausea, and for various reasons it was two years before something was done about it. We then discovered that our dilapidated teaching rooms were lined with asbestos and the university was not aware of its presence. For none of this was I ever required to fill in a risk assessment form.

According to the set procedure for funded travel, I need to assess the risks of being in Japan. In cities a car cannot even cross a pavement without the presence of one or two uniformed characters waving flags to alert passers-by. For crossing roads, Japanese urban designers afford pedestrians the same status as traffic, with ample margins of time, wide crossings and perfect signage. I was once in a coffee bar in Japan when there was a magnitude 6.8 earthquake. Elsewhere it might have caused major devastation; in Sendai, people in the coffee bar did not even stop reading their newspapers.

A colleague who intended to do fieldwork in Turkey was required to produce a personal evacuation plan to be used if there were a major earthquake. Clearly, such a plan would be immediately invalidated by disruption to normal transportation schedules. Now if a repeat of the 1923 Kanto earthquake were to occur while I happened to be in Tokyo, I doubt very much whether the risk assessment would help me. I would have to resort to awareness and common sense.

Despite these musings, risk assessment is, of course, not useless. The problem is that procedural rigidity constrains us to use methods for harmless travel that are the same as those that apply to dangerous experiments and surgical operations. No doubt if I were travelling in eastern Ukraine or Yemen I would dedicate myself more willingly to considering the risks, but not for places where risk assessment effectively cannot help.

The possible solution to this state of affairs would be to divide risk assessment into two. For genuinely risky enterprises the approach would be technical and scientific. The odds of a mishap would be calculated and, where possible, reduced. For un-risky work, a different approach is needed. In this case, the principal value of risk assessment is to ensure, as far as possible, that the university is not sued. Perhaps, then, we should leave it to the lawyers to fill in the forms.

If, gentle reader, this diatribe should strike you as being mere petty complaining, please consider the wider implications, those beyond the shadow of lawsuits and injuries (however faint that shadow may be). Our principal motivation for being academics is to exercise our creativity. However, before collecting data we need data protection registration, ethical approval, deposition of itineraries, risk assessments and more. As we all know, similar bureaucratic loads apply to teaching. The effect of all this form-filling-in is to sap our creativity. Colleagues complain to me that they lack the energy to do real academic work after a day of grappling with poorly designed software intended to collect information that no one really wants, or dealing with procedures that merely add another layer of complexity to what was once a simple, refreshingly human activity.

We watch with alarm at the way bureaucracy grows unstoppably in our universities, how processes that are ostensibly designed "to make our work easier" are instead piling on the burden. And, of course, no one in the university has ever conducted a risk assessment of the impact of the bureaucracy!