Vajont is located about 100 km due north of Venice in the eastern extension of the Italian Dolomite Mountains, a part of the Alpine arc. It is also situated on the boundary between the Italian regions of Veneto and Friuli Venezia-Giulia. The Vajont valley is an eastern lateral tributary to the Piave River, which flows into the Adriatic Sea northeast of the Venetian lagoon. The area is renowned for the First World War battles that were fought at various locations there.

In the late 1950s,

SADE, the regional hydroelectric company, prepared to build a dam on the Vajont

stream. The location, close to the outlet of the valley, was chosen because it

was the site of a deep, V-shaped defile in hard rock. The structure was to be a

double-arched concrete dam built up with pre-cast concrete blocks. A

double-arched structure throws the pressure at the upstream side of the dam

onto the shoulders of the valley and can thus be a very strong solution that

resists destruction by exceptional forces. The intended purpose of the dam was

to regulate the flow of water to electrical turbines on the Piave River by

ensuring a supply at times when the main river was at low flow.

During the construction of the dam a sizeable landslide occurred in the valley upstream. Upon completion, at 262.5 metres from floor to rim, it was the highest concrete arch-dam in the world. In 1960, as the water began to be impounded, there was a 700,000 cubic metre landslide into the reservoir on the south side, which is dominated by the vast bulk of Mount Toc. Various measures were taken to monitor and control slope stability, but they proved ineffective. On 9th October 1963, at 22:39 local time, a 240 million cubic metre landslide dashed into the reservoir from the flanks of Mount Toc, travelling at about 100 km/hr.

The mechanism of the Vajont landslide has been vigorously debated ever since. It was a sturzstrom, according to the term coined in 1930 by the eminent Swiss geologist Albert Heim. At the time only about 60 examples of sturzströme had been documented in the world. The phenomenon was controversial and poorly understood. Essentially, the larger the moving mass, the lower the basal friction, which is counter-intuitive in terms of basic physics. The Vajont landslide slid as a sort of gigantic mattress on a smooth plane of rock.

The material cascaded into the lake and produced a water-wave 180 metres high which climbed the opposing slope of the valley and obliterated the hamlet of Erto, as well as damaging a few houses in Casso, located further up the slope. Frantic efforts had been made to reduce the water level behind the dam, but it was only about 30 metres below the lip. The landslide-generated wave was about 100 metres high as it abruptly changed direction from northwards to westwards. It was thus 70 metres high as it gushed into the Piave valley straight towards the town of Longarone. It obliterated the town, with the exception of very few buildings located at some distance from its centre. The wave then roared down the Piave valley, destroying eleven small settlements as it went. At Vittorio Veneto, 44 km away, it was still six metres high.

Some 1,917 people were killed, most of them instantly, by the water wave. The dam survived with minor damage to its rim. The reservoir ceased to exist, as it was now filled with rock debris from the landslide. A small lake survives to this day 2 km upstream. Longarone was rebuilt, largely by emigres who returned from working abroad and elsewhere in Italy. The dam remains as a sombre monument to the disaster. It is visible from Longarone and its environs in the Piave valley.

In essence, the disaster was caused by a series of bad and unsustainable decisions about the stability of the Alpine landscape in the Vajont valley. The strata on Mount Toc are, to use a useful Italian term, a franapoggio, orientated in the direction of the slope in a way that provides a ready slip surface for overlying material. There were low-strength zones at depth. Filling the reservoir increased the pore-water pressure at the base of the slope, which decreased its strength. Finally, as subsequent research has revealed, sturzströme are not uncommon in the Alps.

Over the years after the disaster, a constant stream of geologists and engineers visited the site, which remained largely undisturbed, forlorn and peaceful in its terrible grandeur. It is particularly awe-inspiring in the cold, grey light of winter. A memorial park, mass-burial cemetery and two chapels were constructed. Marble tablets at the access tunnel to the dam commemorated the loss of life. In Longarone a documentation centre and small museum were built, along with a civil protection training centre.

Recently, the site of the disaster has been opened up to tourism, with a visitor centre, guided tours and a protected walkway across the rim of the dam. The valley has begun to lose its air of abandonment and isolation. Moreover, on the evening of the 60th anniversary of the disaster (9th October 2023), 170 theatres in Italy held manifestations, plays and readings, with a collective pause at the moment of the tragedy, 22:39 hrs. This was specifically designed to keep the memory alive and help people who are too young to have lived at the time of the disaster to know about it. The theatre performances drew upon a rich heritage of books, studies, memoirs, plays and music that over the years has commemorated the Vajont tragedy. There is also a major cinema film about the disaster, with spirited performances by actors representing the main protagonists, including the engineers and geologists involved in planning and designing the reservoir and dam.

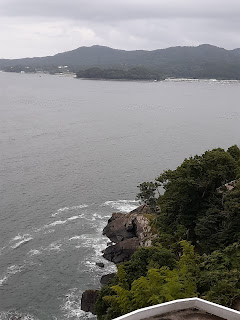

In the aftermath of disaster there is often a tension between those who want to commemorate the event and those who want to forget it, or to obscure the memory. For example, in Lombardy 200 km away from Vajont lies the Stava valley, where in July 1985 the collapse of two mine tailings dams led to a mudflow which killed 264 people. For years, efforts to create a documentation centre and memorial at the site were routinely blocked. At the other end of the scale, in the Tōhoku region of northeast Honshu, Japan, there are now 62 museums dedicated to the March 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear release. For better or worse, this is an area in which disaster tourism has come to stay.

Surely we would all agree that to avoid repeating errors of response and mitigation it is important to learn the lessons of disasters, and that in order to do so we need to keep the memory of such events alive. Yet researchers have also described a phenomenon called 'dark tourism', which tells us that people can have good or bad motives for wanting to visit the sites of past disasters. This is a complicated matter, as it is difficult to define what is good and what is bad. Nevertheless, some of the 'disaster tourists' may be mere sensation seekers while others are motivated by a more noble desire to learn and to confront the realities of life.

With 60 years of hindsight, it is very clear that a large reservoir dam should never have been built at Vajont and that the tragedy resulted from appalling negligence in allowing that to happen in an area of steep, unstable slopes, fractured geological formations and a highly exposed population. A remarkably similar disaster had occurred in France in 1959 with the collapse of the Malpasset dam and the loss of 423 lives. Once again, superficial geological and geotechnical survey work was at the heart of the calamity. Unfortunately, similar tragedies have continued to occur (witness the Derna, Libya, dam collapses of September 2023) and have sometimes been narrowly averted (as in the Whaley Bridge, Derbyshire, emergency of August 2019, which necessitated the evacuation of 1,500 residents from downstream. On balance, it is useful, not only for us all to hear these stories, but for us all to think carefully about what they mean in terms of human safety in the future.